Preparing a multinational expedition is not a trivial endeavour and cannot be done alone or in isolation. In forming the idea that Palawan could be a suitable location for the gene conservation project, the background work started.

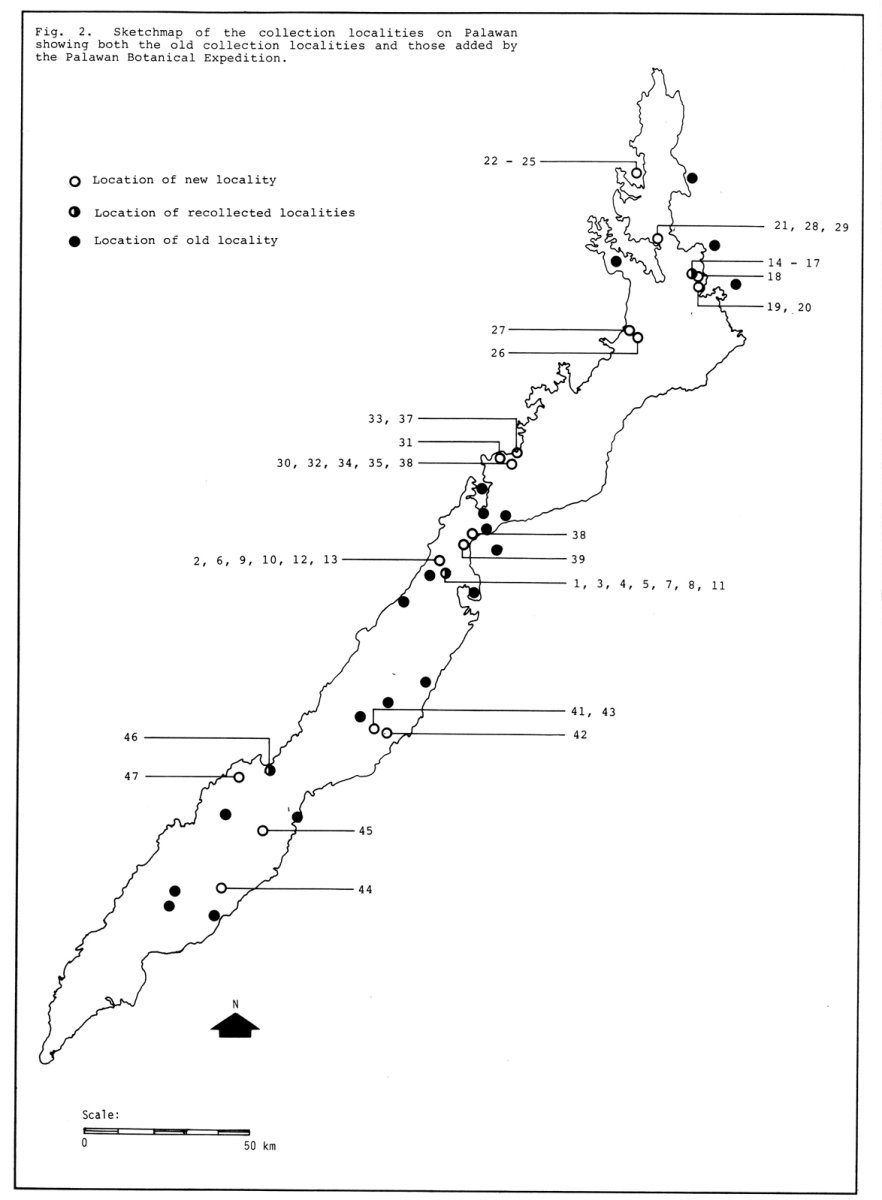

A full literature search for references relating to Palawan together with searches for herbarium material from Palawan enabled a map of unexplored regions to be made. As the literature and specimens spanned over a hundred years, the synonymy of all the plants and trees had to be researched to bring all identifications to the same level. I this way a checklist for Palawan was created (and at that time ISIS did not exist!)..

Landsat 4 imagery for Palawan was acquired from 1982. This was used to identify untouched forest (dark red). These areas were the became the short-list of areas to investigate. In the image above, Mt. Beaufort is nearly central.

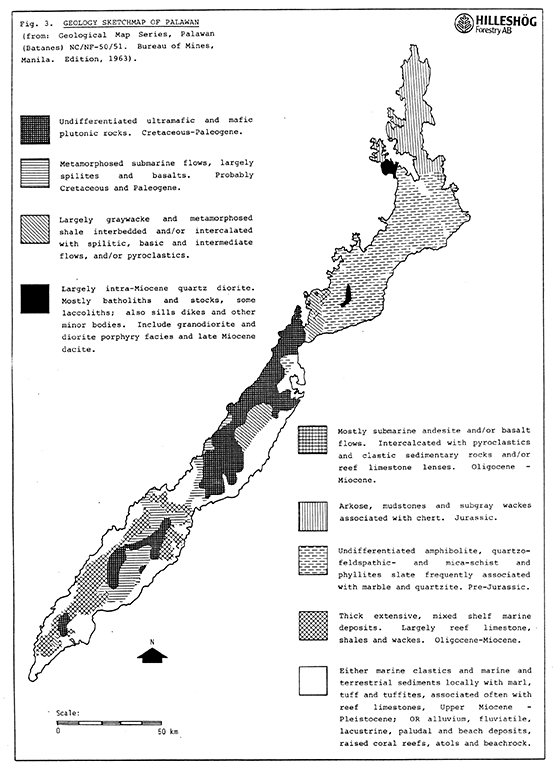

Geology also played an important role in our selection of potential collection areas. Here we matched the untouched areas with the islands geology and chose areas that had different geologies.

During the investigation, contact was taken up with the Philippine National Herbarium, FORI (Forest Research Institute in the Philippines), the Riksherbarium in Leiden (world centre for Malesian botanical taxonomy), the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, the Forestry Department in Oxford and UNESCO. UNESCO had started a project to evaluate Palawan for international conservation status and were working together with Hunting Technical Services for field studies. All groups shared information freely and on agreement with funding, the Rijksherbariums was chosen as the scientific home for the expedition because of their wide and deep knowledge of rainforest botany. They provided a permanent expedition member, and the Philippine National Herbarium and Kew provided specialist team members for shorter periods of time. A professional horticulturalist also joined the expedition from Hannover University in Germany.

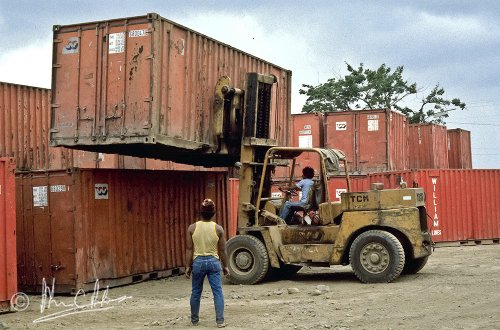

The Philippine National Herbarium and FORI agreed to make local contacts. We had the backing of the Hilleshög AB in Manila, and they arranged the transport of the specialist supplies we needed from Sweden, an expedition vehicle and supplies from Manila that could not be purchased on Palawan, e.g. industrial alchohol.

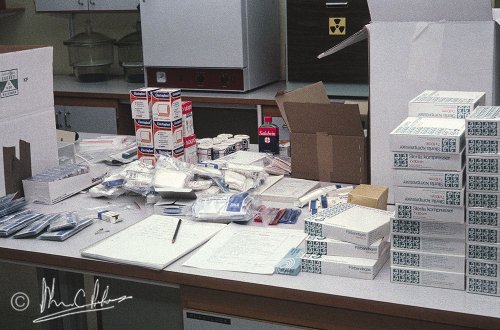

As a member of WEXAS, I was able to get a lot of information on what needed to be thought of when planning a large expedition to remote areas. One important topic was health. With no way of calling anyone in 1984, a lot had to be prepared for. Cuts and bruises, broken bones, snake bite (cobras, tree vipers), intestinal parasites, insect bites (huge centipedes, spiders), highly toxic caterpillars and all three species of malaria had to be considered. There was resistance to different anti-malarials, so a cocktail of anti-malarials had to be taken. It could be up to nine days before professional help was available, and the consequences of that had to be factored in. We had professional medical advice from both doctors and surgeons. We were lucky with almost everything thankfully. No one was injured.

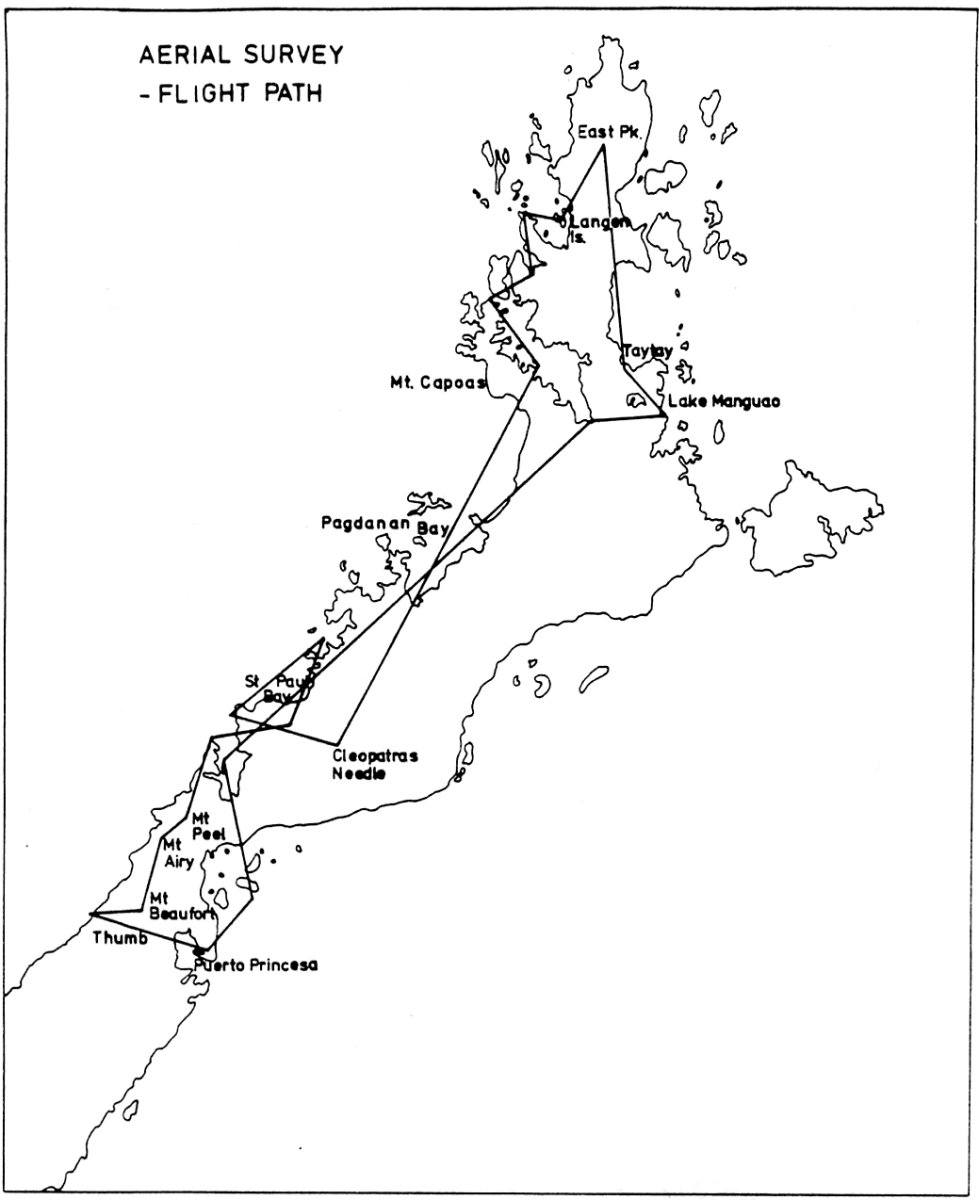

Once we reached Palawan, we established a base in a local hotel, took everything out of the containers that were waiting for us, and contacted the local office of FORI. They provided us with contacts for a driver, cook, three professional tree climbers and a forest camp manager for the first forest camp. We discussed local security and the status of forests on Palawan with FORI. They suggested that an reconnaissance flight over central and northern Palawan would let us refine our selection of locations to investigate

I of course took a large number of photographs of the forest and we refined the locations we wanted to visit. You can see those below.

With all the background work done, the supplies out of the containers and stowed locally, the local work donee could start to pack the four-wheel drive transport that was now out of its' shipping container.